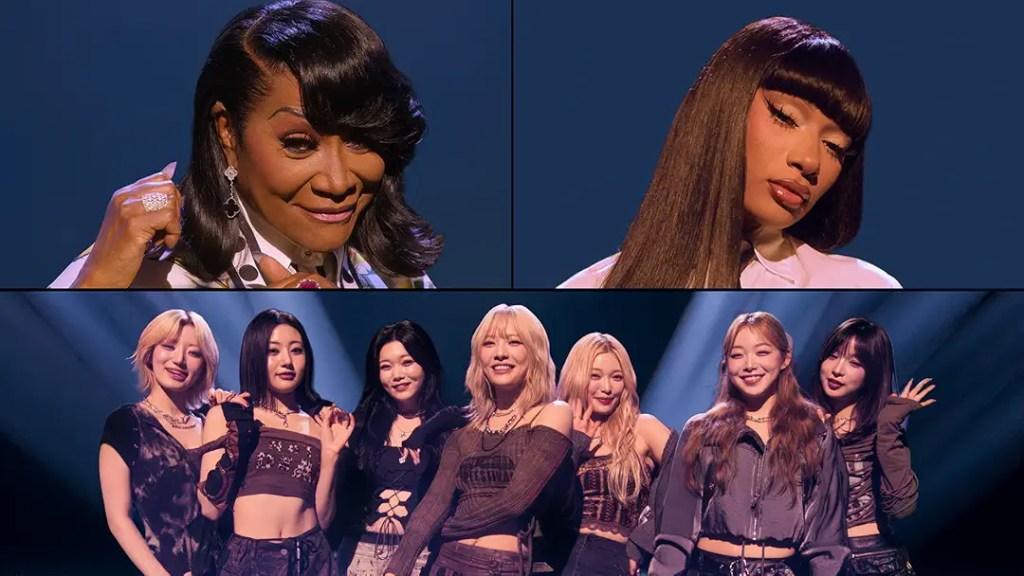

KPOPPED is a 2025 Apple TV competition series that pairs Western pop artists with K‑pop groups to perform remixed songs for a live Seoul audience, who then vote on their favorite performances. Hosted by Soojeong Son and starring Gangnam Style’s PSY and Houston’s Megan Thee Stallion—who also serves as an executive producer alongside Lionel Richie and Korean media company (CJ ENM)—the show positions itself as a celebration of cross‑cultural exchange. Featuring artists such as Patti LaBelle, TLC, Boyz II Men, Vanilla Ice, Boy George, Kesha, and others, KPOPPED works best not as a competition, but as an introduction to Korean culture for Western audiences and as an implicit tribute to Black-American music that shaped K‑pop itself.

Each episode foregrounds cultural encounter: Western artists are paired with K‑pop groups like ATEEZ or Billlie, who introduce them to life in Seoul before collaborating on stage. These moments—walking through markets, sharing meals, rehearsing choreography—offer brief but meaningful glimpses into how K‑pop is lived rather than merely consumed. Yet the show’s strongest episodes go further, using performance to trace the lineage between Black American music and modern Korean pop.

That lineage is most powerfully illustrated through the presence of Black artists whose influence is often taken for granted. Patti LaBelle’s episode is emblematic. Despite her global impact since the 1960s, this was her first time performing in Korea—a belated recognition of her international significance. Paired with Billlie, LaBelle performed a remixed version of “Lady Marmalade,” a song many of their viewers likely associate with the 2001 rendition by Mýa, Lil’ Kim, P!NK, and Christina Aguilera. What the episode quietly reveals, however, is that LaBelle first recorded the song in 1974 with her girl group, alongside Nona Hendryx and Sarah Dash. The collaboration thus functioned as more than nostalgia: it reinserted LaBelle into a pop genealogy that younger girl‑group fans may not know they inherited.

Girl‑group history emerges as a recurring thread throughout the series, with acts such as TLC, the Spice Girls, Blackswan, Kep1er, Kiss of Life, ITZY, and STAYC. These artists open a conversation about collective labor, loss, and endurance. In TLC’s episode with STAYC, the group discussed the legacy of Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes, who died in 2002 in Honduras. Acknowledging her role within TLC’s history resonated across generations and borders, particularly for STAYC, whose six members—Sumin, Sieun, Isa, Seeun, Yoon, and J—navigate similar group dynamics under intense industry pressure. These moments remind viewers that the girl‑group model is not interchangeable or ahistorical; it is built on shared struggle and sustained collaboration.

Such recognition matters, especially in a cultural moment marked by polarization and historical erasure. Black American music is frequently globalized without being contextualized, while Asian histories are often framed as recent or derivative. In EP 2, Vanilla Ice remarked that he could not have imagined collaborating with Korean artists when he was age 16, citing the perceived “modernity” of K‑pop. Yet Korean artists have appeared on U.S. charts since at least the 1950s, when the Kim Sisters—Sue, Aija, and Mia—performed American songs like “Charlie Brown” on U.S. television despite not speaking English. That song, notably, originated with the Black music group, the Coasters. Ignoring Asian‑American history, in turn, obscures Black musical influence.

While K‑pop’s global visibility has surged only in recent decades, its foundations are much older. Groups like Sobangcha in 1987 blended Korean music with American genres, and Seo Taiji and Boys in the 1990s helped establish the blueprint that defines contemporary K‑pop. Western surprise at the genre’s sophistication often reflects historical ignorance rather than genuine novelty. In this sense, KPOPPED unintentionally exposes the need for Western artists—and audiences—to reckon with musical histories beyond the U.S., Europe, and Australia.

Cultural appreciation also surfaces through language and representation. Boy George’s decision to sing in Korean during his collaboration with STAYC stood out as a deliberate act of respect rather than novelty. His eccentric performance underscored the importance of linguistic effort and visibility, particularly for queer artists. The episode subtly suggests the need to support openly queer K‑pop idols such as Holland, Jiae, and Harisu, whose presence challenges industry norms. Elsewhere, the show captures artists immersing themselves in Seoul—J Balvin at a night market, Boy George at Suguska Temple, the Spice Girls sharing traditional tea, Megan eating at the CU Ramyun Library, and Ava Max in on Hongdae Street—images that humanize cultural exchange beyond the stage.

Still, KPOPPED requires a critical lens. The series too often assumes that spectacle alone can carry cultural meaning. Rather than fully contextualizing Black musical history, Korean pop development, or the artists’ personal trajectories, the show skims the surface. This is a missed opportunity. Deeper storytelling—paired with thoughtful commentary from the hosts—could transform impressive performances into moments of genuine education. For instance, TLC’s Tionne “T‑Boz” Watkins has spoken publicly about performing while living with sickle cell disease. Stories like hers would resonate deeply with viewers managing chronic illness and remind audiences that pop stars are not machines, but people.

The show briefly touches on the complexities of K‑pop training, particularly in Kiss of Life and Jess Glynne’s episode, but only scratches the surface. In EP 4, Kesha’s conversation with JO1, a Japanese group, about independently producing “Joyride” for her album Period offered a rare critique of industry exploitation. Although viewers were likely looking at the clock tick with this song choice, watching her assert artistic control against a predatory and abusive system was liberating. Potentially, this inspired K-pop idols operating within one of the most meticulously manufactured music industries in the world.

Ultimately, KPOPPED stands out less for its competitive format than for its potential as a platform for global pop dialogue. Viewers invested in the vitality of Black music will find particular value in episodes featuring Patti LaBelle, Eve, Mel B, TLC, and Boyz II Men. Fans of remix‑driven shows like That’s My Jam, RuPaul’s Drag Race, or Carpool Karaoke may also enjoy the series. Still, the competition itself feels unnecessary. A future season would benefit from shifting focus toward cultural history, K-pop music production, and personal stories from artists.

Finally, the show should broaden its representation. Only one pairing featured an Asian‑American artist—Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas from TLC with STAYC. Including more Black and Asian-American artists would strengthen the show’s premise, as they deserve recognition on the stage in Asia. While this blog reflects my POV in the U.S., it would be great to learn more about each individual K-pop idol. KPOPPED begins a larger, ongoing conversation about how K-pop music can educate, historicize, and connect audiences worldwide. If the series continues, its greatest success will depend not on who wins, but on what histories it chooses to tell.

Leave a comment